Inside the State of RCM Report: Why AI Success Now Depends on System Design

Healthcare has reached a strange moment: AI is finally delivering real operational improvement, yet many organizations still feel stuck. Not because the models are weak, but because the system they are asked to operate inside is fragmented. The 2026 State of RCM report captures that shift plainly. AI has moved into everyday operations, and the industry has moved past the “does it work” debate. The question now is whether it can scale without turning operations into a patchwork of tools, exceptions, and governance overhead.

Proof arrived in 2025, and it is measurable

This is not an early experiment phase anymore. In 2025, 63% of organizations reported AI integrated into at least one workflow. More than half expanded AI across departments, and nearly half put AI governance and ethics structures in place. Those are not the signals of a pilot conversation. They are the signals of an operating reality.

And the outcomes are no longer abstract. Leaders report up to a 40% reduction in documentation time, 20–25% fewer denials through revenue cycle AI, 45% faster scheduling, and 30% lower call center volume. These are meaningful improvements in the places healthcare feels pressure most: capacity, cash, and access.

The biggest blocker is not budget, talent, or model trust

With adoption and outcomes becoming real, it would be easy to assume the remaining barriers are predictable ones: funding, staffing, or skepticism about models. The report points to something more structural. Sixty-two percent of leaders cite fragmented data systems as the top barrier to scaling AI.

That statistic matters because it reframes the problem. Fragmentation is not a temporary constraint that fades with time. It is an architectural condition. Clinical, financial, and operational data still live in separate systems with different formats, ownership, and workflows. When AI lands on top of that, it can deliver wins in pockets, but it struggles to behave consistently across the enterprise. In that environment, AI does not automatically create coherence. It often inherits incoherence.

Why 2026 is an inflection point

The report frames 2026 as the fork in the road. AI will either become a unifying operating layer or it will widen sprawl. The difference is not model sophistication. It is whether organizations standardize on systems that connect data, governance, and workflows instead of stacking disconnected point tools.

That is the risk of AI sitting on top of broken data. It can produce uneven outcomes, higher governance burden, and a growing surface area of operational complexity. Early success does not disappear, but it becomes harder to expand, harder to repeat, and harder to trust.

Why the “levels” matter and why autonomy is a journey

One mistake healthcare can make in this moment is treating autonomy like a switch. It is not. It is a progression.

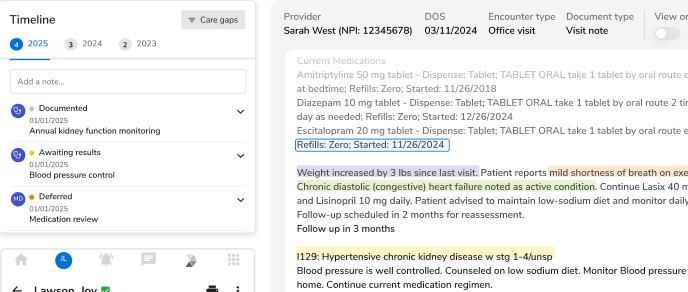

The report describes maturity in levels for a reason: moving from basic experimentation to reliable autonomy requires stepping stones that build confidence, safety, and repeatability. Early levels tend to focus on isolated use cases and task automation. Mid levels look like assisted intelligence, where AI supports staff decisions and speeds up individual steps. Higher levels look like orchestrated operations, where AI can carry routine work end to end with humans focused on exceptions, oversight, and redesign.

This gradual movement matters because each level forces a different kind of readiness. Governance needs to mature before autonomy expands. Data has to be unified before workflows can be orchestrated. Teams have to trust the system before they stop building workarounds around it. Trying to jump from “tools that assist” to “systems that run” without those foundations usually creates exactly what leaders fear: inconsistency, risk, and sprawl.

The point is not to race to the highest level. The point is to move deliberately, so value compounds instead of resetting with every new tool.

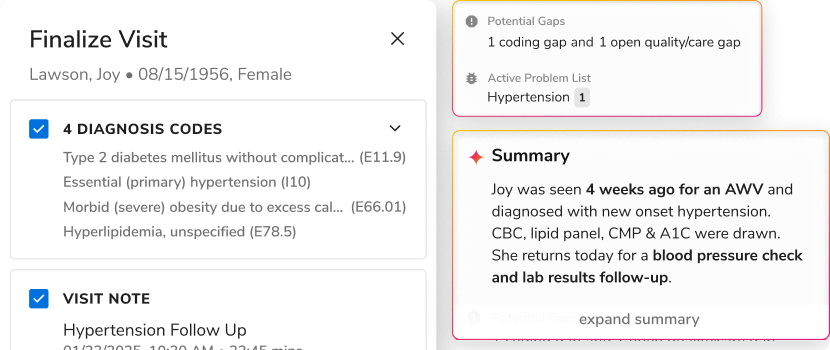

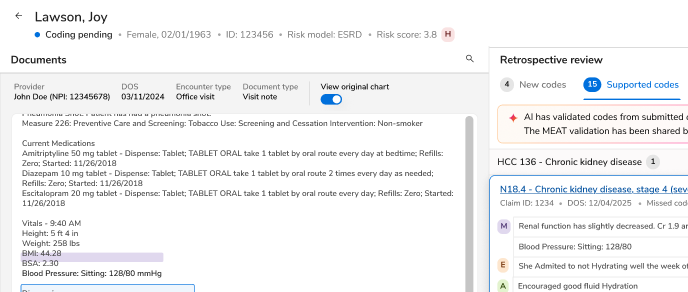

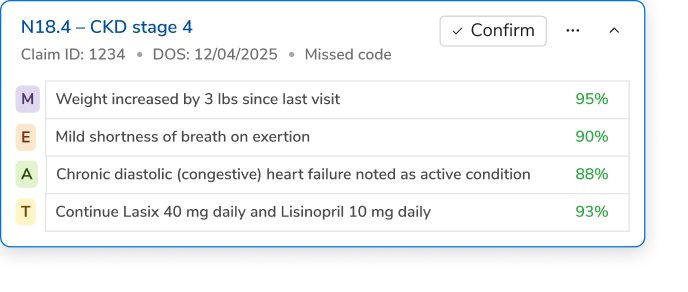

Administrative autonomy is emerging, and revenue workflows are where it will prove itself first

If clinical AI is often discussed in terms of potential, administrative AI is increasingly discussed in terms of proof. The report’s most grounded observation is that the next meaningful leap comes from administrative autonomy, especially across the revenue lifecycle. These workflows are high volume, repeatable, measurable, and deeply tied to margins. They also expose whether AI can operate end to end rather than in isolated steps.

This is the difference between assistance and autonomy. Assistance makes work faster. Autonomy changes how work runs. Autonomy does not remove humans. It removes the need for humans to be the glue between disconnected systems. It shifts teams from constant manual stitching to exception handling, oversight, and redesign.

System design is the new strategy

The report’s investment priorities for the next 12 to 24 months reflect this shift. Workflow and revenue cycle automation leads the list, but it sits alongside predictive analytics, governance, unified data platforms, and EHR or CRM copilots. That combination signals a move away from standalone tools and toward infrastructure: systems that can orchestrate work, manage risk, and scale consistently.

It also explains why system design is now a leadership issue, not just a technical one. In the next phase of healthcare AI, strategy is not defined by what models can do. It is defined by what the organization can operationalize reliably.

Closing thought

AI has crossed the adoption threshold. The decisive question is no longer whether AI works, but whether it will be cohesive or chaotic at scale.

In 2026, the advantage will not come from running more pilots. It will come from making a small number of high-impact workflows boring, reliable, and repeatable across the enterprise. That only happens when the underlying system is designed for AI to operate like infrastructure, not as a loose collection of tools.

Read more about the findings here: https://innovaccer.com/state-of-revenue-lifecycle-in-us-healthcare-2026

.png)

.png)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)