Transforming Oncology: The Shift to Value-Based Care [Part 1/2]

Cancer doesn’t wait. Every delay in diagnosis or treatment increases the risk of mortality - and for some cancers, even a four-week delay can raise the death rate by 6% to 8%. And yet, for far too many patients, providers, and health systems, care delivery feels like it’s stuck in the past - fragmented, reactive, and financially unsustainable.

Over the past decade, oncology practices across the country have faced growing tension between what is medically possible and what is economically viable. The statistics tell a sobering story: cancer care costs are projected to exceed $246 billion annually by 2030, yet patient outcomes and experience metrics haven't improved proportionally with this massive investment.

We’re at a crossroads in oncology, where breakthrough treatments collide with broken payment models. Precision therapies are emerging, but without structural reform, they’re being delivered through systems that weren’t built to support them. If we don't act now to redefine how we measure, deliver, and pay for cancer care, we risk undermining the very progress we’ve made.

This is not just a financial problem - it’s a moral imperative.

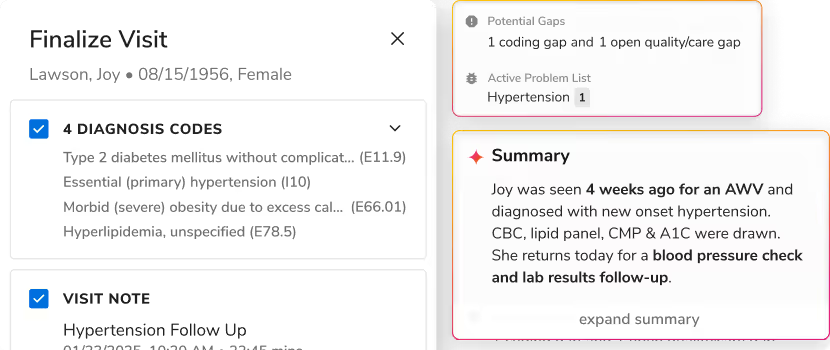

The Broken Economics of Cancer Care

The economics of oncology present a profound paradox: as spending skyrockets, value diminishes. Think about this - Americans are shelling out over $200 billion annually on cancer treatments, yet we're not seeing survival rates or quality of life improve at the same pace. Something doesn't add up, right?

.png)

(Source)

The human cost here is staggering. We've actually had to coin a new term - "financial toxicity" - to describe what happens when cancer treatment destroys a patient's financial health. I've seen patients who are 2.5 times more likely to file for bankruptcy than people without cancer. Many are emptying retirement accounts or selling their homes just to stay alive. And here's the truly heartbreaking part: when patients worry about money, they often skip treatments or cut pills in half. Their chances of survival actually decrease - talk about adding insult to injury.

The problem sits with how we pay for cancer care. Our fee-for-service model basically rewards doing more stuff, not necessarily better stuff. I've watched oncologists struggle with impossible choices: prescribing that $15,000-a-month drug that might add a few months of life while knowing it could financially devastate the patient, or limiting options based on what someone can afford rather than what might help them most. Meanwhile, hospitals and practices are bleeding money on complex cases, especially for Medicare and Medicaid patients.

And then there is fragmentation! Cancer patients bounce between specialists, hospitals, and imaging centers like pinballs. Each handoff creates another opportunity for things to fall through the cracks - or for duplicate tests that nobody needs. To top that, a large part of what we spend goes toward pushing paperwork rather than fighting cancer.

The way things are going isn't working for anyone. Patients get financially toxic care with mediocre outcomes. Providers burn out under administrative burdens while struggling to keep practices afloat. And insurers watch costs spiral with little improvement to show for it. If we don't fix this now, all these amazing new precision therapies will just make things worse - breakthrough innovations that fewer and fewer people can actually access.

Value-Based Oncology: Beyond the Buzzwords

Let's cut through the jargon and talk about what "value" actually means when someone's life is on the line. In boardrooms and policy papers, "value-based care" gets tossed around like everyone agrees on what it means. But in oncology, value looks radically different depending on where you sit.

For patients, value is deeply personal. It might mean living long enough to see their kids graduate, maintaining independence, or avoiding debilitating side effects. I remember speaking with a breast cancer survivor who told me, "I didn't care about my five-year survival statistics. I cared about making it to Tuesday's dance recital without throwing up from chemo." Patients value transparent costs, coordinated care, and being treated as a whole person - not just a collection of symptoms or a billing code.

For oncologists and care teams, value means having the right tools and time to practice medicine the way they were trained. Many clinicians I work with feel crushed between documentation demands and productivity metrics, with precious little time for actual patient care. They want systems that help them make evidence-based decisions without drowning in administrative tasks. Most importantly, they want their clinical judgment respected rather than overridden by formulary restrictions or insurance denials.

For health systems, value increasingly means financial sustainability amid rising drug costs and shrinking margins. A community cancer center director recently confided, "We lose money on half our patients. How long can we keep our doors open like this?" Systems need predictable revenue flows and ways to manage risk that don't punish them for taking on complex cases.

For payers, value means demonstrable outcomes that justify premium costs. They're asking legitimate questions: Does that $150,000 treatment actually help patients live better or longer lives? Could the same results be achieved with less expensive alternatives?

So why has aligning these perspectives proven so difficult?

The path forward isn't creating more buzzwords or pilot programs that fizzle out. It's building pragmatic frameworks that balance these competing definitions of value and tackle the fundamental disconnects in how we measure, deliver, and pay for cancer care. The practices getting this right aren't just checking regulatory boxes - they're fundamentally reimagining the entire patient journey from first symptom to survivorship or end-of-life care.

In Part 2 of this series, I'll explore how innovative oncology practices are making this vision a reality through data-driven approaches, breaking down information silos, and embracing digital transformation that genuinely improves patient outcomes while creating sustainable business models. The future of oncology depends not just on scientific breakthroughs, but on delivery models worthy of them.

.png)

.avif)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)