From There to Here

Missed our previous post? We suggest you start here,

with “Introducing Healthcare Valuenomics”

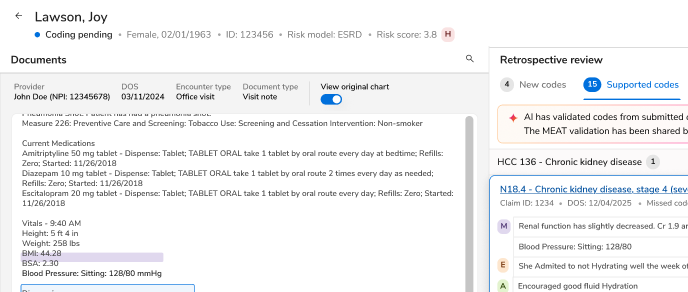

In my last article, I introduced “Valuenomics 101: General Principles of Managing Risk.” Today’s article continues to cover these general principles, and starts by answering the question:

How We Got Here

In most industries, businesses operate in a relatively free market. They succeed by delivering goods or services that customers want at a price they’re willing to pay while also managing costs.

The healthcare industry is different. US healthcare providers have been insulated from normal market forces for a long time because of the intermediary role insurance plays in negotiating prices and reimbursing claims.

Putting aside the virtues or benefits that public or commercial insurance offers in terms of affordability, access, utilization, and administration, the fact that a third-party negotiates the prices and pays the bills means patients and providers don’t need to think about price or quality (value) when they make decisions about care services. It’s a classic principal-agent problem.

For example, when a patient with a knee injury visits a doctor, they don’t normally worry about the price or quality of an MRI, hospitalization, surgery, or rehab session if they have insurance coverage. They assume the quality of the procedure will be high, and the only financial factor that might give them pause is the expense of a deductible or co-pay.

Likewise, under fee-for-service medicine, the doctor has no financial limitations in providing care unless specific services aren’t covered or authorized by the insurer. In fact, the hospital or clinic wants the doctor to schedule as many diagnostic tests, procedures, visits, and so on as possible, because that will bring in more revenue—even when those services may be unnecessary or, in some cases, potentially harmful.

How did we get to such a strange place?

Commercial insurance first became prominent during World War II with the expansion of employer-based coverage. The Federal Government imposed wage and price controls to keep labor costs down but allowed companies to offer health insurance benefits to attract workers.

US healthcare expenditures began to rise in the 1950s, as care costs increased. Since many people (specifically the elderly and poor) didn’t have employer-based insurance, Washington launched Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 to increase affordable access to care. From that point forward, healthcare expenditures really took off, as the graphic below illustrates.

Figure 2: Rise in US healthcare expenditures since 1929

CMS (Medicare) makes the final decision for how much doctors and hospitals will be reimbursed for a particular procedure.Through Medicaid, the States pay even less than Medicare. Hospitals typically charge commercial insurers significantly more for the same procedure, depending on their market power, to make up for the shortfall on government reimbursement.

This has complicated the business of healthcare significantly. Within a given hospital, the same service will be reimbursed differently, depending on whether the contract is with Medicare, Medicaid, or (now) Medicare Advantage, or based on rates negotiated with any number of commercial insurers.

While in theory, lower payments from Medicare and Medicaid should reduce the overall cost of care, it hasn’t in reality.

Figure 3: Traditional roles payers, providers, and patients play in healthcare

That’s because FFS payments reward providers for the volume of services they deliver, regardless of whether they’re being reimbursed by Medicare, Medicaid, or commercial insurers. As a result, providers can increase revenues by delivering more services.

Commercial insurers are not as incentivized to reduce those costs as you might think because their profit is based on a percentage of the total cost of care. Meanwhile, employers, despite footing the bills, have limited influence over how much care their employees use or how much providers charge.

That’s clearly a recipe for increasing costs without necessarily improving quality. And that’s exactly what we’ve seen over the past century. Today, US healthcare costs more per capita and the costs are rising faster than healthcare in any other wealthy country, but we achieve average or worse performance on many key measures, including life expectancy and overall health.

Attempts at Value

For decades, CMS has been trying alternative business and payment models in an attempt to figure out how to pay for value instead of volume as a way to curb costs and improve quality.

One effort emerged in the 1980s when CMS introduced DRGs (diagnosis-related reimbursement groups) to pay for procedures, as opposed to the number of days patients spend in hospital.

The intent was to put hospital stays in the cost column, rather than the revenue column. But as a result, hospitals started discharging patients as early as possible to reduce those costs, even when it wasn’t medically appropriate.

To curb that practice, CMS introduced financial penalties in 2012 for hospital readmittance. They also experimented with bundled payment programs that reimburse providers for predetermined costs of clinically-defined episodes of care, rather than leaving those costs variable and up to the provider.

Another approach, the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), was launched in 2012 to enable Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), which earn financial incentives by reducing costs and meeting quality goals—basically, by better managing population health.

In November 2022, CMS issued its final rule to give low-revenue ACOs some upfront financial support and more time to adjust to the complexity of downside risk. This is the biggest reform to the program since it was implemented and is expected to increase participation particularly in rural America.

The same CMS rule also cuts FFS Medicare payments to most providers for 2023. Their overarching goal is to have every Medicare beneficiary (63 million and counting) be enrolled in a value-based care program by 2030.

Progress toward value-based care will be picking up speed. But FFS will likely remain a dominant model for some years to come.

Aligning Interests and Incentives

Commercial plans got into value-based care (VBC) for their own reasons. Their motivations can be best understood with simple math. Let’s say an insurer gets around $400 premium on a given member, by regulation, they must spend most of that $400 on care costs—typically around $350. Of the remaining $50, about half goes to administrative costs and half becomes profit.

Health insurers soon realized that if they invest in care management services (that guide plan members to lower cost services and their own narrow provider networks), they can reduce care costs and increase profits. The problem, however, is that plan members don’t respond well to being told by their insurer where and how to receive their care. Patients trust their doctor more than their insurer.

So payers turned to providers for help, offering them a share of whatever savings could be earned by directing patients to lower cost, high-quality care services. Why would providers want to give up any of the fee-for-service (FFS) dollars they were being paid by insurers? Because entering a risk-based contract with an insurer helps the provider gain a greater portion of a patient’s healthcare dollar.

For example, patients can spend their healthcare dollars with a variety of providers. This means that of the $350 the insurer pays in claims for that patient, only some of that money (let’s say $170) will go to a specific provider.

The provider can invest some marketing dollars to increase that portion from $170 to $190, earning them an extra $20. And they can help reduce the total cost of care from $350 to $330, which will earn them half of the savings, or an extra $10. As a result, if a provider masters Healthcare Valuenomics, they can earn an extra $30 per patient by participating in both FFS and VBC contracts.

Intrigued? I’ll pick this up in my next post, where I’ll cover Healthcare’s Business of Risk, and dive deeper into how Valuenomics can help you master the rules of risk to deliver better results regardless of the payment model in play.

.png)

.avif)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)