Healthcare’s Risky Business

Missed our previous post? We suggest you start here,

with “From There to Here”

Today’s article continues to explore the general principles of managing risk, this time bringing the business model of risk management into sharp focus. We’ll see how Healthcare Valuenomics can help you scale risk management across payment models effectively.

Healthcare’s Business of Risk

Many health system CFOs, steeped in FFS, have found it hard to adjust to a process that’s a bit like playing three-dimensional chess. For example, under FFS, the CFO isn’t motivated to do anything to reduce readmissions unless they are penalized by CMS for very high readmissions for a particular diagnosis-set. But under a value-based contract, it pays to reduce readmissions.

That’s topline thinking. If CFOs want to optimize their bottom line, a case is to be made that an $18,000 readmission makes $180-300 profits for a health system in the FFS world, but if that same readmission did not happen makes $9,000 topline through value-based care and potentially $3,000 in profits. That’s 10 times more profit in VBC than FFS.

Regardless of the payment model, providers that understand how Valuenomics works can do very well. Valuenomics offers a mindset for thinking about the levers of financial performance. As a framework, it can be applied to any economic model, including FFS, because it gives practitioners the discipline to identify and influence meaningful revenue drivers. The insights Valuenomics generates become even more important within value-based care models because revenue drivers are more complex, and providers must also manage risk.

Why is risk a part of the equation if the main objective of value-based care is to reduce costs? Providers participating in value-based models take on some risk when they treat patients. If they lower costs and improve quality they get paid more. If they don’t, they get paid less. Most providers only participate in upside risk, meaning they are rewarded for succeeding at lowering costs and improving quality but don’t take a financial hit if they fail. Providers who share in upside and downside risk earn more—but they must understand and master the rules very well to succeed.

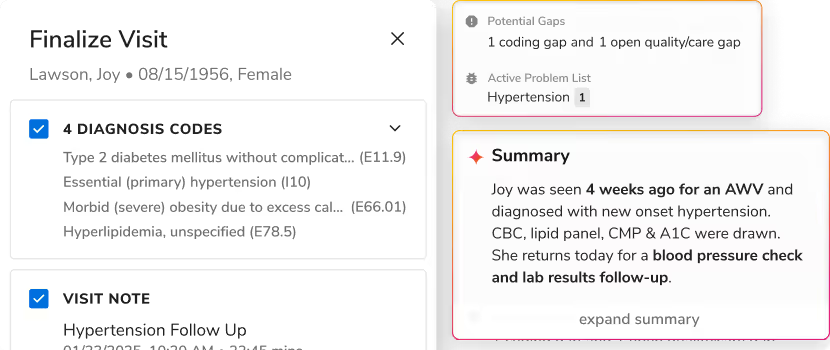

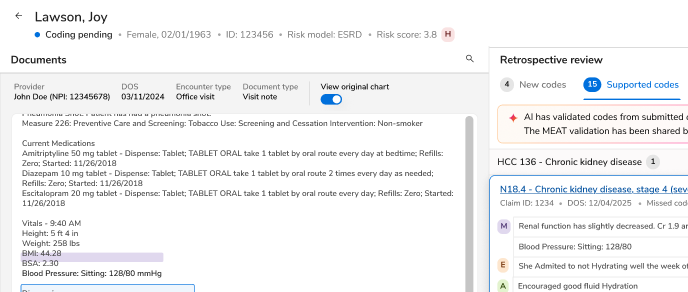

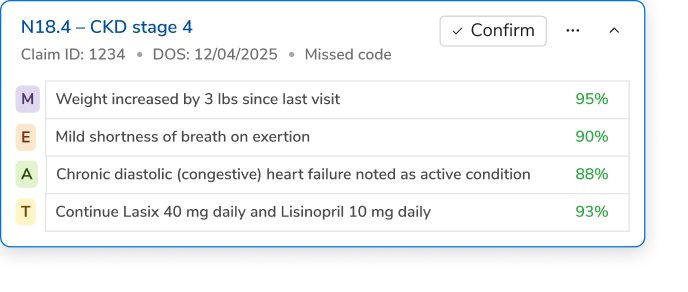

Risk models are based on disease states that set benchmarks for the cost of care. The average patient starts with a risk score of 1.0. A patient with diabetes, on the other hand, might have a risk score of 1.2. This means their benchmark cost is $1,200 instead of $1,000. Any reductions in cost the provider can make in treating their diabetes will earn them more “Shared Savings” if the patient has a higher risk score.

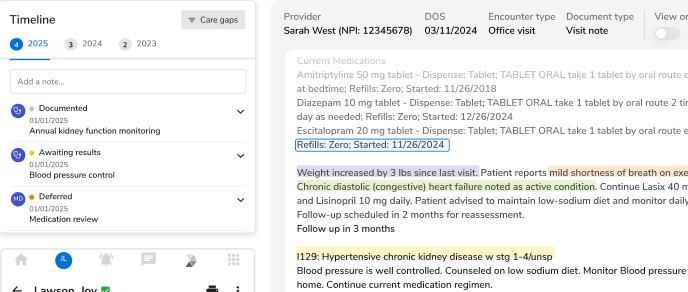

The problem is that every year the scores are reset. If a provider doesn’t document a patient’s diabetes or cancer every time they visit (even for an unrelated issue), their risk score and benchmark cost will be reduced. Providers that master the multidimensional complexities of managing risk well document every observed condition to accurately increase risk scores and benchmark costs. Those that don’t master these complexities inadvertently deflate their risk scores, and reduce their cost benchmarks.

Quality Qualified

If the process was just about improving risk scores and reducing costs, patients would be in trouble. As with Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs), providers would reduce the volume or cost of services they provide and call it a day. The patient and the healthcare system would eventually pay a price, however, when that patient’s health status worsened and costs ballooned. To offset that perverse incentive, the CMS introduced a quality component into their alternative reimbursement models.

Measuring quality is complicated, given the variety of diseases and treatments. To establish consistency, CMS determines what is the best practice for a given condition, and sets standards for quality care.

For example, diabetes can be assessed with an A1C test—also known as the hemoglobin A1C or HbA1c test—which measures average blood sugar levels over the previous 3 months. When A1C test results are within a specific range (typically below 7% or an average glucose level of about 154 mg/dL), the provider is doing a good job helping the patient manage their diabetes and keeping them healthy. They’ll receive a better quality score as a result.

In the end, it’s the provider's job to determine which services will help the patient manage their diabetes, and whether the costs of those services are worth the payoff.

The Rise of Value-Based Care Organizations

Unfortunately, individual providers find it too complex and burdensome to document risk and report quality measures while managing costs. They just want to practice medicine. And so ACOs have stepped in to create an administrative entity for a coalition of providers that will assume that burden.

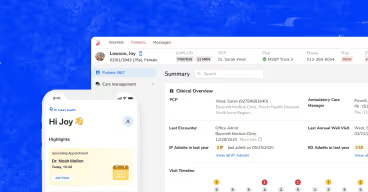

ACOs Driving Value-Based Care

Figure 1: Introducing ACOs into the healthcare ecosystem

An ACO will contract with a payer on a shared savings contract on behalf of its providers. It will take some administrative fee for managing that contract, but it will pass the rest of the savings onto the providers. It’s up to the ACO to determine the mix and quality of providers that will earn the best portion of shared savings.

ACOs have tried a variety of structures, models, and incentives across many different regions of the country. There are hospital-sponsored ACOs set up as a subsidiary of a health system. There are independent physician ACOs and health-insurance sponsored ACOs. There are employer-based ACOs and pay-for-performance risk based arrangements.

Each arrangement type can be executed across the risk continuum from upside only to full downside risk. Shared Savings are determined by the benchmark cost minus the actual expenditure multiplied by the type of arrangement.

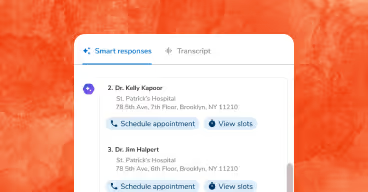

Value-Based Contract Structure

Figure 2: Formula for calculating shared savings in value-based contracts

The structure of the contract includes a number of important variables, including the population being managed, the costs that are being controlled, how savings are calculated, how the payer determines benchmark costs, how shared savings are calculated and whether there is a minimum threshold, and whether expenditures are determined annually or truncated based on cohort.

Likewise, the contract will include quality stipulations, such as: Is quality performance a barrier to shared savings? How does the quality multiplier affect shared savings? How does the provider group get pay-for-performance revenue?

This equation, if broken down further with a double-click, leads to 12-14 value levers. Value-based care organizations must know how to master these levers, like bases in baseball, as bases lead to runs and runs get you wins. Then there are specific value levers that can be manipulated to improve the contract payout, some of which are more important to prioritize over others. To succeed at these contracts, a provider must:

- Understand how different types of value-based contracts function

- Identify the incentive methodologies in question

- Calculate the total incentive potential for your current customers

In subsequent posts, I’ll show you how to develop business cases for particular value levers, how to compute a single number to identify high-value and low-cost players, and describe real-world strategies for using those levers to effectively increase shared savings while still managing the complex and even contradictory incentives of traditional fee-for-service arrangements often at work within alternative payment models.

I’ll also show you where most healthcare organizations following best practices are actually missing the “Moneyball” aspect of managing care and costs. The secrets of Healthcare Valuenomics will be revealed on a case-by-case basis.

Success in those endeavors will be determined by how well you understand Healthcare Valuenomics to calculate the cost, quality and risk variables of a value-based contract.

Cover the Value Lever Bases

Figure 3: Valuenomics—the art and science of mastering these value-levers

In my next post, we’ll look at Valuenomics in Practice: Wrestling with 30-Day Readmits, where we’ll answer the intriguing question, “Why Wednesdays? I’ll also show how health systems can use analytics to figure out which measures to dig into, reveal simple yet profound factors that impact performance, and use this intel to drive continuous improvement.

.png)

.png)

.avif)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)