Is Our Public Health Data and Analytics Infrastructure Ready for the Next Threat?

As of early January 2025, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is reporting an increase in the epidemic trend of influenza and COVID-19. As we enter the peak season for respiratory-related illnesses in the US, many healthcare leaders continue to question whether our public health data and analytics infrastructure has evolved to meet the challenges of today and beyond.

Lessons From the Past

It is well known that the COVID-19 pandemic exposed various shortcomings in public health data and analytics infrastructure.

Consequently, the legacy public health data and analytics infrastructure hindered healthcare professionals and first responders from effectively collecting and sharing data with organizations across the public health ecosystem. This undermined efforts to more effectively understand and respond to the pandemic as organizations struggled with:

- Gaining real-time transparency into pandemic KPIs, trends, and outcomes

- Quickly designing/deploying effective, equitable mitigation, and treatment strategies

- Delivering insights into the effectiveness of current/future programs and policies

- Reducing the likelihood of avoidable health disparities

Building a Bridge to the Future Since the pandemic, we have made great strides toward modernizing our data and analytics infrastructure. Below are just a few of the primary initiatives that have helped build a more reliable future for public health data and analytics:

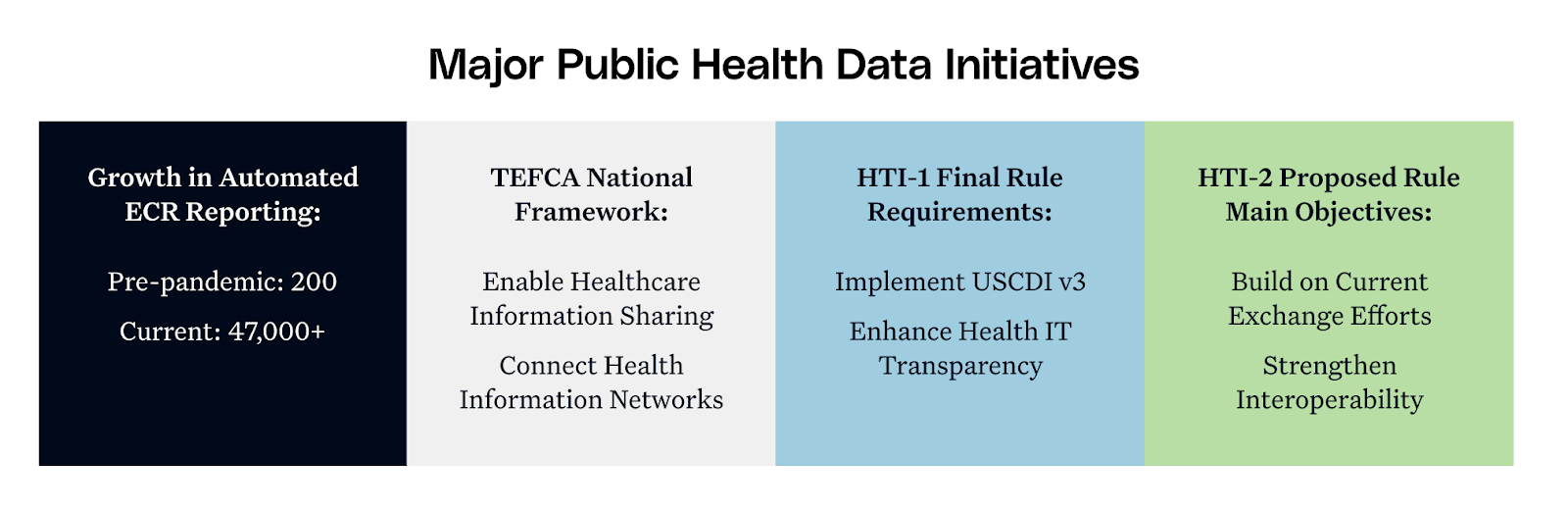

- ECR Reporting: Before the pandemic, less than 200 healthcare facilities leveraged automated electronic case reporting (ECR). Fast forward to January 2025, and over 47,400 have systems in place for sending automated ECRs, providing public health officials with quicker insights into disease trends.

- Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA): TEFCA, originated by the US Department of Health and Human Services Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy (ASTP), is a national effort to enable and promote healthcare information sharing across the existing/new health information networks in the US. Qualified Health Information Networks (QHINs), which can represent a variety of healthcare organizations, such as public health agencies, healthcare providers, HINs, health information technology vendors, and payers, are larger health information networks that execute a Common Agreement with the Recognized Coordinating Entity (The Sequoia Project). The result is a national framework for exchanging healthcare data where all participating organizations who align with a QHIN can share information.

- Health Data, Technology, and Interoperability: Certification Program Updates, Algorithm Transparency, and Information Sharing (HTI-1) Final Rule: Requires certified health IT developers to employ United States Core Data for Interoperability Version 3 (USCDI v3), helping to promote public health interoperability efforts. It also provides enhanced transparency into the use of certified health IT to support public health data exchange and update ECR reporting standards/implementation guidelines.

- Health Data, Technology, and Interoperability: Patient Engagement, Information Sharing and Public Health Interoperability (HTI-2) Proposed Rule: The proposed rule would seek to build off of current exchange efforts (HTI-1 and others) further strengthening public health interoperability efforts and improving public health data exchange. It would seek to expand the number of healthcare facilities exchanging data with public health agencies and help provide more accurate and reliable insights into public health threats.

Significant Work Remains Despite Current Efforts

Funding

Though considerable progress has been made we have miles to go before we come close to meeting expectations. While the CDC’s multi-billion, multi-year Data Modernization Initiative is in place, the BCHC reports that only 29% of large local health departments have received additional funding for their data modernization projects.

Estimates from HIMSS show that truly reforming the current public health data infrastructure will require a massive investment of as much as $36.7 billion over the next 10 years. Funding is needed to address a variety of issues that continue to plague our nation's public health data/analytics infrastructure today.

The Path Forward: Policymakers at the federal, state, and local levels must continue to recognize the vital importance of continuing to fund public health data/analytic infrastructure improvements. Additionally, opportunities exist with other government agencies such as Medicaid to collaborate with public health organizations and leverage policy/program initiatives such as Medicaid Enterprise Systems and 1115 Demonstration Waivers to improve Medicaid beneficiary outcomes and the effectiveness of public health initiatives.

Data Fragmentation

Our current public health ecosystem continues to be highly decentralized, suffering from severe data fragmentation. The CDC, for example, operates 100+ different disease surveillance systems while many state, tribal, local, and territorial Public Health Authorities (STLT PHA) take their own technology solution approach to supporting disease surveillance and many other public health functions.

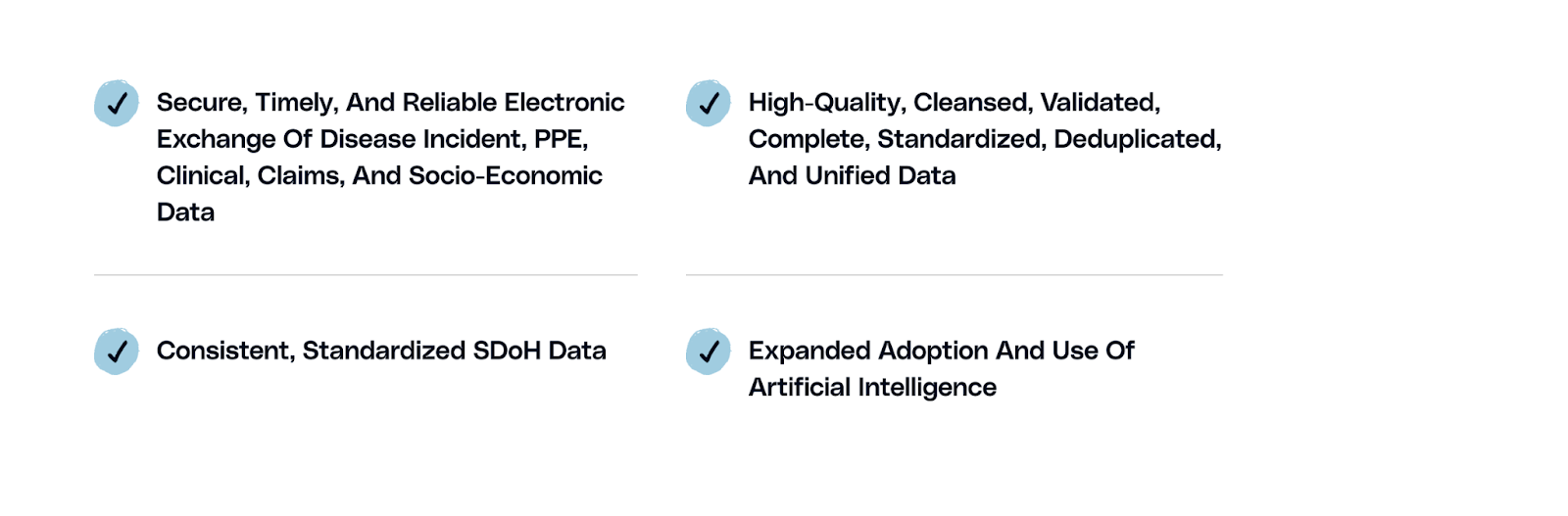

The Path Forward: While data may be fragmented, it does not mean it can’t be unified and better leveraged. Data from different sources, such as STLT PHA disease surveillance systems, CDC, EHRs, HIE’s, laboratories, homeless management information systems, and more, can prove much more vital when effectively and reliably unified.

Contemporary technology solutions use advanced analytics and machine learning/AI to quickly and efficiently ingest data from a variety of siloed sources. They clean, validate, standardize, deduplicate, and unify data to form a complete 360-degree view of citizen health. Unified data can provide more holistic transparency into public health, fuel new initiatives such as social health information exchanges and/or modernized disease management and surveillance systems, and ultimately help all stakeholders better understand and respond to emerging public health threats.

Data Completeness and Standardization

Incomplete data presented a massive challenge during the pandemic and persists today. Early pandemic reporting in 2020 showed that over 55% of race & ethnicity data was missing from COVID-19 case data. Even after the issues were widely public, a 2022 analysis showed that about 36% of a CDC COVID-19 database (~50 million cases) still lacked race and ethnicity data. Another 2023 study showed more than 60% of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data was missing in adult EHR patient records.

These issues present an incomplete picture of diseases and their impact on different population segments, resulting in avoidable negative outcomes and health disparities. Additionally, data standardization continues to be a significant issue with many healthcare providers and public health agencies using different systems and data collection/reporting standards. The United States Government Accountability Office called out data standardization as one of their top areas of opportunity to improve public health data management efforts.

The Path Forward: Public health data can be sourced from a variety of different sources, systems, and locales. Stakeholder representation across these ecosystems must continue to collaborate and drive efforts to agree on common data standards. As initiatives such as those within HTI-1, HTI-2, and TEFCA take shape, the hope is that more momentum will be gained towards standardization efforts.

There must also be a commitment to expanding/improving data collection efforts at the point of service. Professionals at the point of service are often not well-enabled to collect data such as SDoH and may not be trained on how to explain their importance in a culturally sensitive manner to patients.

Interoperability/Data Exchange

The same BCHC study referenced earlier showed that a staggering 96% of its respondents indicated they were struggling to effectively exchange data with state health agencies. This could be due to incompatible systems (legacy/outdated), insufficient interoperability development support (skill levels, headcount, etc.), and a lack of support for contemporary interoperability exchange standards such as FHIR.

Interoperability challenges make it difficult to effectively track health trends and outcomes. For example, in our current system, COVID-19 and Influenza (notifiable conditions) patients who visit a healthcare provider/lab may trigger an initial notification of their condition to STLT PHA/National Surveillance systems. However, because different healthcare providers, labs, and STLT PHA’s could all be using different systems and exchanging standards, there is a chance that data may be in an incompatible format with an STLT PHA system. This may lead to an error-prone manual case capture or the possibility of data never being captured at all. Other problems may also be present such as a mismatch of data exchange standards/formats resulting in data irregularities (unreliable/misunderstood demographic data such as race/gender/SOGI) and/or poor matching efforts to track case activity across the same patient.

The Path Forward: The public health landscape includes thousands of systems with different data analytic infrastructures used by healthcare providers, labs, pharmacies, public health agencies, health systems, insurance companies, and community organizations. These systems come from many different vendors, were built in different time periods, and are tailored as per the needs of each organization.

Government-led initiatives such as CMS-9115-F, CMS-0057-F, HTI-1, HTI-2, and TEFCA will continue to provide the groundwork for much-needed interoperability progress while industry efforts to evolve FHIR and other standards that support interoperability will also prove vital. Technology vendors continue to press the edge of innovation and those who provide standards-based, open, API forward systems will act as a central nervous system for complex, multi-system environments that promote and encourage interoperability and the secure exchange of healthcare data.

Limited use of Artificial Intelligence

Despite the potential of Artificial Intelligence (AI) to improve public health data analysis, adoption in public health departments remains limited. According to the National Association of County and City Health Officials’s (NACCHO) Public Health Informatics Profile 2024, around 76% of local health departments (LHD) hesitate to use AI. This is especially concerning for larger jurisdictions serving populations of over 500,000 or more. Also, most organizations employ AI for communication purposes only. This gap in usage prevents public health agencies from leveraging the power of AI to quickly identify patterns/trends, optimize resource allocation, and predict the impact of mitigation measures and clinical interventions.

The Path Forward: Selected examples to leverage the power of AI:

- Early Warning Public Health Alerting Systems: Emerging public health threats can occur at any time, as we learned with COVID-19 we seemed to consistently be operating a step behind and generally more “reactionary” than “proactive”.

The sheer number of data systems/sources that can flood in can prove near impossible for a human to effectively triage and raise alert flags about potential threats. Advanced AI can be deployed to monitor, triage, identify, and alert stakeholders to potential emerging public health threats and help us be more “proactive” in the future.

- Resource Optimization: The pandemic brought about one of the biggest resource challenges the world has ever experienced. First responders, health professionals, government employees, and workers across many other professions during the pandemic were left scrambling to react to a massive public health threat and constantly shifting mitigation strategies and employee/public needs.

- AI resource optimization models can play an essential role in enabling organizations to use a machine learning-driven solution that can dynamically adapt to the surrounding environment variables and provide proactive recommendations on optimization strategies to achieve organizational goals. Such solutions can also provide opportunities for stakeholders to execute simulation models and evaluate “what-if” scenarios.

- Policy/Program/Intervention Simulation Modeling: During the pandemic and even today, many public health organizations appear to struggle with performing extensive, proactive simulation modeling on the effectiveness of programs, policies, and interventions. As organizations seek to stay ahead of public health threats they do not have extensive time to spare while designing/developing programs, policies, and interventions.

They must look to leverage AI-driven solutions that can provide real-time intelligence into the possible outcomes using advanced simulation modeling and “what-if” analysis. This will enable public health stakeholders to more expeditiously evaluate and deploy mitigation strategies and quickly recalibrate models to consider new data/variables/scenarios/goals.

- Disease Surveillance: Public health agencies are generally severely underfunded and constantly seeking to “do more with less”. As disease surveillance systems continue to go through an evolution process and the volume/variety/velocity of electronic case data continues to increase there may be significant challenges with triaging the data for quality concerns, matching/deduplication, and analyzing data for trends, demographic/geographic variation, and other potentially impactful insights.

Where these challenges can cause delays of days/weeks/months, AI models trained on sound data management processes can identify, flag, alert, and potentially remediate issues in real time, and AI-trained surveillance agents can operate as additional public health “eyes” seeking key, impactful insights and alerting public health stakeholders in real-time.

Closing Thoughts

The pandemic taught us many difficult lessons. Consequently, we have done much to improve our public health data/analytic infrastructure. However, significant progress is still needed to achieve a state of modernization that can truly support proactive responses during times of new/emerging public health threats. In efforts to coordinate funding, data unification/completeness/standardization, interoperability/exchange, and the use of artificial intelligence, collaboration will be critical across the entire public healthcare ecosystem. Public health agencies will need to work closely with sister agencies, healthcare providers, payers, community-based organizations, technology developers, and many other private partners to drive towards success and our goal of being best prepared for the next emerging public health threat.

.png)

.avif)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)