Valuenomics in Practice: Wrestling with 30-Day Readmits

Missed our previous post? We suggest you start here,

with “Healthcare’s Risky Business”

Why Wednesdays?

That was one of the head-scratching questions we asked ourselves when looking at how the volume of 30-day readmits impacts administrative effectiveness, care outcomes, and financial performance in different health systems. Why did care coordinators, tasked with keeping post-acute patients healthy and out of the hospital, connect with fewer patients on Wednesdays?

I’ll keep that a tantalizing secret for now, but the answer—which might at first seem trivial or unimportant in the grand scheme of a hospital’s complex array of operations and workflows—is illustrative of the kind of insights that Valuenomics will reveal, and the perspective and mindset it sharpens. Hidden differentiators of performance, once discovered, can have outsized impact on a health system’s prosperity.

By now I assume (and hope) you’ve read the first five posts in this series, you now have a basic understanding of the principles of Valuenomics. Going forward, I’ll show how Valuenomics works in practice, alternating between applying its principles with value-based care models (typically Medicare, Medicare Advantage, or chronically ill patients) and fee-for-service care models (usually commercial and healthier patients).

| Day | # of outreaches | % successful |

|---|---|---|

| Monday | 398 | 89% |

| Tuesday | 365 | 73% |

| Wednesday | 363 | 57% |

| Thursday | 338 | 77% |

| Friday | 313 | 75% |

Fig. 1: Actual analysis that raised the question, “Why Wednesdays?”

Showdown at the OKR Corral

Many health systems and other healthcare organizations are still learning to adopt performance indicators and measures that are fairly standard in other industries. For example, OKRs, or Objectives and Key Results, is a goal-setting framework used by Intel in the 1970s, by Google in the early 2000s, and popularized by former Intel employee John Doerr in his 2018 book, Measure What Matters.

OKRs are intended to bring focus to differentiating factors. They are improvements or innovations with clear business value, not standard measures of everyday performance like Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). In other words, once identified, OKRs can potentially help an organization significantly improve performance or growth.

For example, a company might establish an OKR around increasing the percentage of sales leads that get closed or increasing the volume of customers with repeat business. To make those objectives real, OKRs need to specify which driving factors or key results contribute disproportionately to those objectives, and work on improving them.

For a health system engaging in value-based care with Medicare patients one of the most important OKRs is 30-day hospital readmissions. CMS established the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) to reduce avoidable readmissions by improving care coordination, communication and engagement with post-acute patients.

CMS measures a hospital’s excess readmissions within 30 days of discharge, according to expected rates for specific disease categories or conditions. It then adjusts payments to the hospital based on the percentage reduction in readmissions the hospital achieves.

So, if 30-day readmits are a big factor in improving reimbursement, then what should a health system’s target objective be? And what results can it focus on to reach that objective?

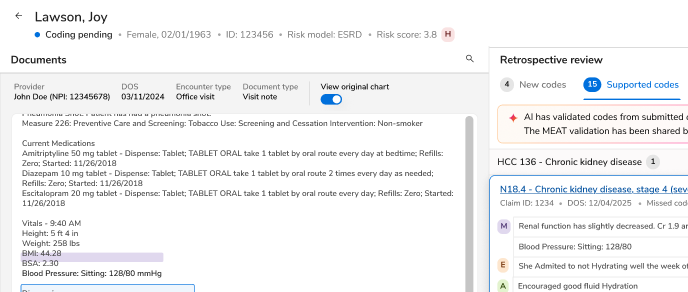

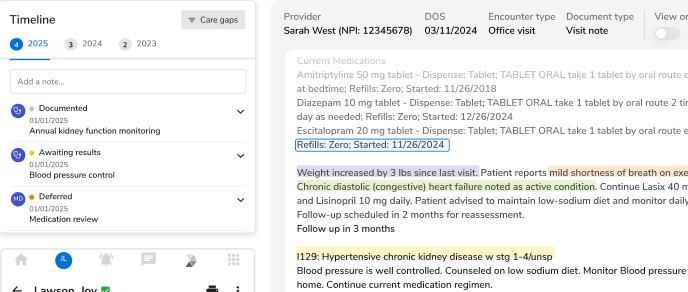

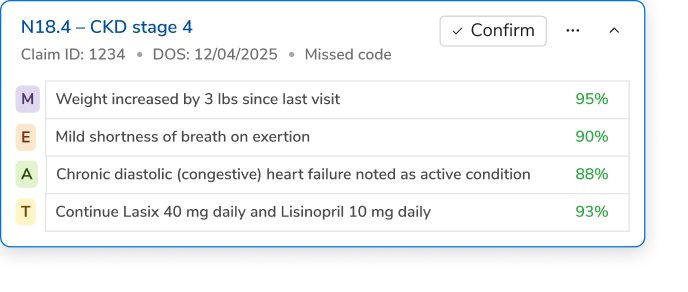

From Outliers to Root Causes

In one case, the health system we were working with had a 30-day readmit percentage of 17.5% for medicare patients. The industry average for Medicare patients is 18%, so that wasn’t a terrible number. And not all readmits are bad. For some patients, returning to the hospital is necessary (and perhaps even anticipated) because of their condition or response to treatment.

But avoidable readmissions drive up healthcare costs unnecessarily and mean something has gone wrong with the patient’s health that, by definition, could have been avoided. Accordingly, this health system set a new goal to reduce its readmissions rate to 14.8%. Six months later, it achieved a 16.8% rate, saving it some money.

That still didn’t meet its OKR, so we dug deeper on how performance could be improved by changes to workflow or approach. Evidence-based best practices in care transition tell us that there are three key factors that reduce 30-day readmissions after discharge. Specifically, a health system must:

- Reach out to the patient within 24 hours of discharge

- Enroll the patient in a transition of care protocol to ensure plan adherence

- See that the patient visits their primary care provider within seven days of discharge

But which are the most important factors that drive better performance? When focused on improving care transition planning, most health systems view performance as a productivity problem. As such, they look at how many patients get called after discharge or enrolled in a care plan (a volume metric) vs. looking at their individual results (a value metric) . This would be like a baseball team that wants to score more runs focusing on the aggregate number of at-bats vs. the outcome of each at-bat. They fail to determine how more runs are actually achieved.

In the case of the health system, the key is to focus on which care coordinators have the best performance, as measured by the percentage of avoidable readmissions prevented on their watch.

30-day readmission rates at a large southeast hospital

Viewed through this lens, the results become eye opening. Of the six nurses we studied, five had readmission rates around 10%. One had a standout readmission rate of 5%. Her name was Mary. She was producing the most runs on the team, but the health system overlooked her value because they were focused on the volume of patients enrolled in care plans.

Given that Mary did the same job as the other nurses, we wondered how she produced more value. We soon discovered the one thing Mary did differently. At the beginning of each call with a patient, Mary said: “I’m here for you for the next 90 days. You can call me for any reason.” And then she provided all of her contact information.

That might not seem like a lot, but that extra, empathetic effort at trust-building clearly had an outsized impact on Mary’s patients, and led to 50% improvement in readmissions rates with her patients. Instead of letting their conditions decline or ignoring small problems with their care plan, they felt free—encouraged, even—to call Mary for help. As a result, they were the group more likely to avoid bigger problems that would lead to unnecessary returns to the hospital.

The Circle of Continuous Improvement

A Valuenomics mindset will make you curious about the real drivers of performance, and give you the objectivity to examine and discover overlooked factors. Once those hidden drivers are revealed, they can usually be amplified or shared more widely. For example, Mary’s generous offer to patients soon became part of the “script” that all care coordinators at her health system now use.

Training other nurses to adopt Mary’s approach cost the health system little to nothing, yet had a profound impact on readmission rates overall. It was reduced to 14% that year and has continued to drop every year since, down to 13% and, lately, to 12%. Yet they would never have discovered this simple but profound outreach practice had they not embraced Valuenomics’ investigative approach. The data was there. The analytics revealed the gap. But analytics can’t always answer “why.” That’s where Valuenomics in practice comes in.

| Care coordinator | TCM assigned | % Successful TCM outreach | % 14-day PCP follow-up | % readmit on successful TCM reachout | % Risk-adjusted readmit on successful TCM reachout |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MARY | 130 | 51% (66) | 53% | 6% | 2.1% |

| Aarushi | 122 | 43% (53) | 55% | 11% | 4.0% |

| Jane | 92 | 34% (31) | 58% | 13% | 4.7% |

| Emmanuel | 15 | 73% (12) | 50% | 17% | 4.7% |

Fig. 5: Actual deidentified analysis of Health Coach details that raised the question, “What is Mary doing differently?”

Other hidden variables can drive performance:

- In another health system, the practice of Valuenomics discovered that one care coordinator had more success because of her close connection to the local Vietnamese immigrant community (she was Vietnamese, too) The health system hired more coordinators from that community and the readmission rate dropped significantly.

- In still another health system, the practice of Valuenomics deduced that the care coordinator always asked to speak to a family member, and drilled down on the patient’s living conditions, including how much food they had in the refrigerator. This prompted conversations around social determinants affecting their health, which could then be addressed.

Then there was the case where the analytics indicated that care coordinators weren’t successfully reaching and connecting with patients on Wednesdays.

Why Wednesdays? Putting Valuenomics into practice, we learned that, in that health system’s state, senior citizens received their meal and grocery discounts on Wednesdays. And what did they do? They spent most of the day shopping or dining out, so they were effectively “Out of Office” for the whole day! The health system made the nurses more effective and improved productivity overall simply by assigning them a different set of tasks on Wednesdays.

By using Valuenomics, a health system can determine its OKRs and use analytics to figure out which measures it needs to dig into, discover the often simple but profound factors impacting performance, and use this collective intelligence to drive continuous improvement. It’s not the volume of activity that matters, but the value of the outcomes you want or need to achieve.

In the case of 30-day readmits, we found that care coordinator performance was the biggest driver. A simple change in the fundamental approach they were taking with patients was all it took to have a high-value impact on performance.

Of course, you need the right technology, data, analytics, and workflows to get maximum value from Valuenomics. All too often, I’ve seen nurses use rulers and pencils to analyze printouts of discharge data, when a data analytics solution could do that analysis for them in a fraction of the time and with much lower error rates. I’ve also seen care coordinators spend too much time manually managing patient outreach when a modern call center solution would be far more effective. And of course, we all need IT systems that can aggregate and normalize data to compare performance effectively.

Fortunately, today, the technology health systems need is readily available. Valuenomics allows you to go beyond dashboards and make the most of today’s advanced data and analytics technology. That’s how health systems can score more runs quickly, easily, and cost-effectively.

So, what performance lever should we look at next? In my next post, we will examine how to identify the highest-value SNFs a to reduce the cost of Skilled Nursing Facilities, and ultimately a network of the highest-quality skilled nursing facilities.

The Valuenomics Series

.png)

.avif)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)