Valuenomics in Practice: Redirecting Traffic at the ED

Missed our previous post? We suggest you start here,

with “Valuenomics in Practice: Sniffing Out Low-Value SNFs”

What’s the job of a hospital Emergency Department (ED)?

That might sound like a simple question with an obvious answer, but I’m asking it for a reason. The late Harvard scholar Clayton Christensen taught us that a service is valuable to a customer because it accomplishes a job they want done. For example, his classic study of a very busy milkshake stand revealed that many customers bought those shakes because they were too thick to drink quickly, which helped pass the time on their long commutes. In that sense, they were actually buying a pleasant distraction, not a refreshing ice cream drink.

Understanding the specific job the customer (or in the case of healthcare, the consumer) is hiring you to do helps your business better meet their needs and keeps them coming back. Thicker milkshakes encourage repeat customers. And the more customers, the better.

But when it comes to EDs, hospitals have a problem unique among business institutions. They would like fewer unnecessary customers and fewer repeat customers. While EDs provide a crucial service and a gateway for appropriate hospitalization, unnecessary ED usage is a major drain on hospital revenues.

Unnecessary ED utilization cost the US healthcare system more than $8.4 billion in 2019, double that of 2010. An estimated 13% to 27% of ED visits could be managed in physician offices, clinics, and urgent care centers, saving the US health system $4.4 billion annually. Complicating matters, the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) mandates that everyone must be treated or stabilized in the ED, regardless of their insurance status or ability to pay.

Every hospital in America is trying to figure out how to reduce unnecessary or avoidable ED visits—especially the super users who single-handedly cost hospitals tens of thousands of dollars a year. That’s why it’s important to channel Clayton Christensen and ask, “What job is a 65-year old white male in the midwest hiring his local ED to do when he visits 40 to 60 times a year?”

The ED Burden on Patients, Clinicians and Hospitals

Once upon a time, patients turned to their family doctor or local pharmacist when they had a sudden injury or worrisome health concern.

Clearly, those days are behind us. Primary care clinics typically have limited hours and aren’t available for walk-in appointments, so they’re not helpful for emergencies or what a patient might consider an emergency (ear ache, fever, back pain, sprain, anxiety, etc.). In fact, last year the typical patient had to wait 21 days to see a family physician. And the average wait time to see a family physician or specialist was 26 days in 2022, up 8% over 2017 and 24% over 2004. This is due to many factors, including a growing shortage of primary care physicians.

So what does a patient do when they or a loved one needs to see a doctor more immediately? Many turn to the closest hospital ED which they know is open 24/7.

Studies show that on average 37% of ED cases are judged to be non-urgent (whether prospectively at triage or retrospectively following ED evaluation) with peak non-emergent visits at 62%. Here are some reasons why that is a problem:

- EDs are expensive. Nearly all EDs operate around the clock; are equipped with a full spectrum of costly medical technology, medicines, and supplies required to provide emergency care; and deploy highly skilled trauma clinicians to meet fluctuating demand. As a result, the average ED visit costs $1,646 compared to only $171 at urgent care—or 853% more than the alternative for visits that don’t need the full capabilities of an ED.

- EDs are overcrowded. Patients who don’t need emergency care—defined as hospital services necessary to prevent the death or serious impairment of a patient’s health—create a bottleneck that affects clinician workflow and diverts resources and attention from those with a genuine emergency need. Since 1980, overcrowding has been identified as one of the main factors limiting correct, timely, and efficient hospital care. And even before the pandemic, more than 90% of US EDs saw capacity pushed beyond the breaking point at least “some of the time.” The impact of ED overcrowding on morbidity, mortality, medical error, staff burnout, and excessive cost is well documented but remains largely underappreciated.

- EDs don’t always deliver care—at all. When EDs have high-wait times due to overcrowding and other factors, such as staffing challenges, patients often leave without being seen (LWBS). It’s a growing problem. Median hospital LWBS rates nearly doubled from 1.1% (0.5%-2.5%) in 2017 to 2.1% (0.6%-4.6%) in 2021. Among the worst performing hospitals in 2021, 10% of ED patients left before a medical evaluation. These departures can have significant health consequences for patients delaying or deferring care for an acute condition, and have quality and safety implications for hospitals. It’s why LWBS rates are often used as an ED performance metric. In addition, hospitals rely on patients with legitimate emergency needs to fill beds and generate revenue. Hospital CFOs closely monitor LWBS ratios as an indicator of lost revenue, because that’s literally revenue walking out the door.

Why do patients visit the ED anyway? For the majority, there are two basic reasons:

- They don’t know or like the alternatives. In addition to an ED or a primary care clinic, a person in need can also receive care through an urgent care clinic (UCC), a retail care clinic, or via telehealth. The number of UCCs topped 9,600 as of November 2019, according to the Urgent Care Association (UCA), with patient volume up 60% from 2019. There are now more than 3,000 retail health clinics throughout North America, a market projected to grow from $2.05 billion in 2022 to $4.22 billion by 2029. And the percentage of physicians conducting telehealth visits grew from 14% in 2016 to 80% in 2022. If patients with non-emergent needs don’t seek one of those available alternatives, it’s likely because they don’t know it’s an option, they still prefer the extreme convenience of the ED, or they hold negative perceptions of providers in alternative care settings.

- They don’t know their copay is higher. Typically, patients have copays somewhere between $100 and $200 for an ED visit compared to the $25 to $60 they pay for primary or urgent care. Given how confusing health plan coverage can be, many probably don’t know they’ll be paying more for an ED visit until they get the bill.

In both cases, the fix for hospitals is relatively simple. With basic information—think posters, automated phone messages, etc.—patients can be informed of better, cheaper alternatives. Most will respond to that information accordingly, and reduce their unnecessary ED utilization.

Yet, some patients don’t respond as expected but persist in using the ED so often that they’re referred to colloquially as “frequent flyers” or “super users”. The definition of such a “high utilizer” varies, but four or more ED visits per year is the most common threshold. Others define high utilizers as those who visit the ED “beyond reasonable use,” have more than one ED visit per year, or who have a number of ED visits greater than the 99th percentile.

If someone visits an ED frequently even when they have no medical need to do so, it’s important to ask why. The answer takes a little digging.

What Valuenomics Reveals Hospitals Should Do

Which brings us back to our 65-year-old white male who goes to the ER an astonishing 40 to 60 times a year. Because he’s on Medicare, there are no copays to incentivize him to go to an alternative UCC or retail clinic. And though he has complex chronic conditions, he has no emergent reasons to be medically evaluated. So why does he go?

An interview with this man reveals the real emergency: He’s lonely. Widowed and living alone, he goes to the ED to receive care, attention, and reassurances from people who recognize him, and treat him warmly when he shows up. He’s willing to wait to be seen, and stays until he’s evaluated.

In this case, the ED thought it was providing emergency medical care; but the consumer was seeking comfort and companionship. The distinction makes all the difference in the world. While high utilizers represent only 4.5-8% of the total number of ED patients, they represent a disproportionate percentage of annual ED visits (21–28%). As a result, high utilizers have a significant impact on ED costs, overcrowding, care quality and safety, revenue loss, recidivism, and EMS resources.

In other words, they’re extremely costly to the hospital across virtually all measures. When we employed Valuenomics thinking to analyze frequent fliers writ large, the elderly white male who suffers from loneliness was just one prominent type we identified. Often, frequent fliers were people who have chronic conditions but are poor planners. They forget to get their wounds re-dressed or their prescriptions refilled during normal office hours, and turn to the ED on weekends or late at night to meet those needs.

The latter group responds well to outreach. Many health systems (especially those operating under value-based models) provide tuck-in services for their chronically ill patients. A nurse might call the patient on a Thursday and ask, “Do you have everything you need for the weekend?” If the patient needs support, the nurse will schedule an appointment at the primary care or urgent care clinic the next day, or a virtual care visit which can be delivered then and there.

In popular culture, in season 1 of New Amsterdam, a homeless patient named Andy visits the hospital more than 100 times and costs over $1.4 million a year for the New Amsterdam hospital. The Dean of Medicine aggressively decides to rent a home for him in New York City, which is much cheaper than visiting ED so many times a year.

These tuck-in services can be automated as well, using healthcare CRM (customer relationship management) systems to deliver a series of medication reminders to patients, letting patients (and even their family members) know that nurses are available after-hours and over the weekend through traditional and virtual channels, and allowing appointments to be scheduled online or through a 24/7 contact center. Patients can be engaged in the manner they prefer, whether that’s through a phone call, a text message, an email, live chat, a portal, and so on. Automating this process also reduces the burden on staff that’s already under pressure due to staffing shortages.

Fewer health systems identify and engage with patients like the lonely 65-year-old white male because they don’t understand those needs as clearly. By identifying that patient’s jobs-to-be-done, the hospital could offer other, less costly solutions that meet his needs more directly. For example, clinicians might refer him to community services or a behavioral health provider (even virtual) to help him manage his loneliness. They also might use tuck-in services to check in on him periodically, and give him the attention and sense of connection he gets by visiting the ED, without incurring the high cost of an ED visit.

We’ve found that a weekly call from a nurse and a monthly primary care visit seems to do the trick for many such patients—and it’s well worth the cost. If 30 visits to the ED at a cost of $2,000 a visit was the norm, that’s $60,000 a year for the hospital. A monthly primary care visit is $200 or $2,400 a year. A five-minute weekly nurse call costs about $40 each time or another $2000 a year. That represents an annual savings of $56,000 for one patient. Multiply that by 100 ED visitors and you’re looking at close to $5.5 million dollars. That doesn’t include the extra benefits that come from reduced patient wait times and better use of clinicians in the ED.

The Technology Advantage

For a simple program, that’s a remarkable ROI. Of course, many of those frequent fliers don’t stop going to the ED all together, but every reduction in non-urgent care volume pays dividends. In the end, reducing avoidable ED use boils down to identifying and engaging high-frequency ED users by meeting their “jobs to be done” in less costly ways.

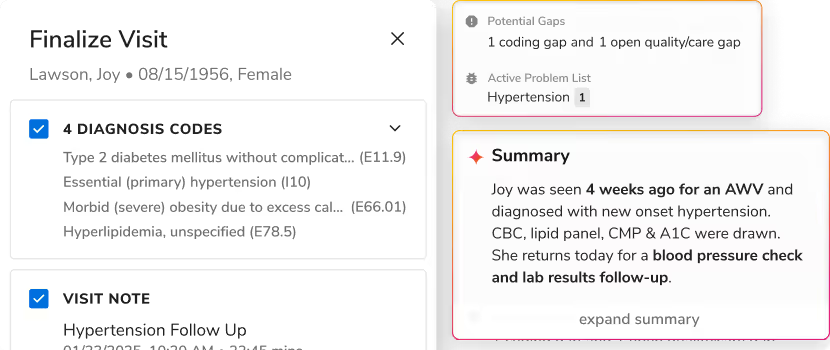

Doing this at scale is the challenge—and one that is typically beyond the reach of the hospital’s EHR. It requires a data and analytics platform that integrates patient data across EHR, HIT systems, and care settings to create longitudinal patient records that are then available for population health analytics to process. Ideally, the clinical data is also integrated with the hospital’s CRM system to facilitate the most efficient automated engagement. The resulting analysis helps coordinate care, education, outreach, personal and digital engagement efforts intelligently and effectively and, most important, can be used to measure and track the impact of these efforts on ED utilization.

For example, data analytics can provide the clinical team with comprehensive profiles of the top ED users on a regular basis (weekly, monthly, quarterly, etc.) to identify case management needs and other opportunities for patient engagement, such as tuck-in services. It can also autonomously drive digital engagement via CRM systems that support clinically contextual (i.e., non-marketing) engagement and outreach, including information on alternatives to the ED.

If the problem and opportunity warrants it, the hospital might also need to invest in more alternative care options (e.g., extended walk-in hours for primary care). ED visits drop by 17.5% when a UCC opens nearby, reducing the total number of uninsured and Medicaid visits to the ED by 21% and 29.1%, respectively.

Valuenomics helps you identify and assess the option(s) that will make the biggest impact. In this case, they are:

- Education and outreach on alternatives and copays

- Data that stratifies and identifies high utilizers

- CRM systems to facilitate efficient automated engagement

- Call centers to provide outreach and tuck-in services

- Investments in convenient, less costly alternative care settings or partnerships with such providers

Which option(s) make the most valuenomic sense for your hospital?

In my next article, I’ll be taking a look at how you can use Valuenomics to plug the leaks on referrals. Stay tuned for that!

Read the Entire The Valuenomics Series

.png)

.avif)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)